“General coverage” receivers (covering most of the useful radio spectrum, from longwave through UHF) have been around for decades, but they tend to be bulky, expensive, and limited when it comes to certain features (including bandwidth and available demodulation modes). More recently, Software Defined Radios (SDRs) have come into prominence, offering almost unlimited reception opportunities, the ability to add features simply by upgrading software, and unbelievably affordable prices.

SDRs are the ultimate tool for exploring the radio frequency spectrum. In addition to covering nearly the entire radio spectrum in a single unit, they provide the unprecedented ability to record large swaths of the radio spectrum in real time, with the opportunity to analyze it later, or even play it back and tune into any signal that was transmitting in that range at the time.

This is my brief guide to the implementation and capabilities of an SDR setup. It is based on my personal experience with two particular models that I own – one (RTL-SDR Blog V3) relatively low-cost, the other (SDRPlay RSP1A) moderately priced (I don’t own any high-end expensive models). Note that this is a very abbreviated overview of some of SDR’s capability – these versatile devices can be put to numerous other uses (documented online, of course).

With a simple wire antenna, these devices can be used like conventional radios to listen to AM and FM broadcasts, and can also be used to listen to international shortwave broadcasts. That’s probably not what you (nor any other SDR user) is really interested in, though (unless you’re into “broadcast band DXing”, which is the hobby of collecting a log of AM and/or FM stations heard from distant locations). The radio spectrum is full of interesting signals, and with a slightly better antenna (and, in the case of digital signals, the proper software – usually available free) the following are a some examples of what you can tune in, listen to, and decode:

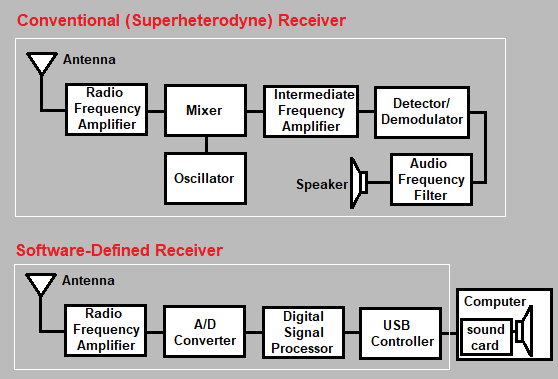

Unlke conventional radios, SDRs don't require a lot of circuitry for tuning, demodulating, filtering and audio processing/amplification; instead, they rely on an external computer's processing power to accomplish these functions (almost always via a USB port), as depicted in the diagram below.

As a result, SDRs are usually very compact. As a matter of fact, the most popular (and least expensive) units are the RTL-SDR (and clone) series of SDRs that are only slightly larger than a USB memory stick!

Most beginners start with an RTL-SDR, given its price, capabilities and wide support. As of this writing, the latest full-featured version is the RTL-SDR Blog V4, available for $30. Be sure to buy it from a reputable source (refer to www.rtl-sdr.com for authorized dealers) as numerous counterfeits that don't function as well are being sold.

If you are looking for a higher-end unit (which will provide better filtering against interference, and wider bandwidth), there are numerous models available; I can personally recommend the SDRPlay RSP1A (around $100) based on my experience, but AirSpy makes some very popular receivers (in the $170 range).

Most SDRs (including those listed above) are compatible with a wide range of freely available software. My personal preference (for ease of use, range of features, and availability of online support) is SDR Console; however, it's only available for Windows at this time. Popular alternatives include SDR++ and SDR# (pronouced 'SDR sharp'), especially for non-Windows platforms. SDRUno, the default software that comes with SDRPlay products, is (in my opinion) clunky to use; however, it does have a scanner feature that's useful (missing in SDR Console), and it's available for alternate platforms (such as Linux, if you're using a processor like a Raspberry Pi 3 or 4, or Linux computer; tablets and phones typically don't have the processor power to run SDR apps).

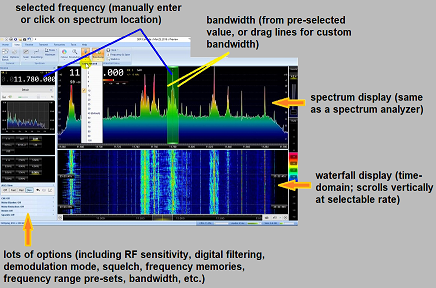

A typical screen shot (from SDR Console) is presented below. It may look complicated at first, but the learning curve is not steep, and again, numerous resources (including tons of YouTube videos) are available online to get you up-to-speed.

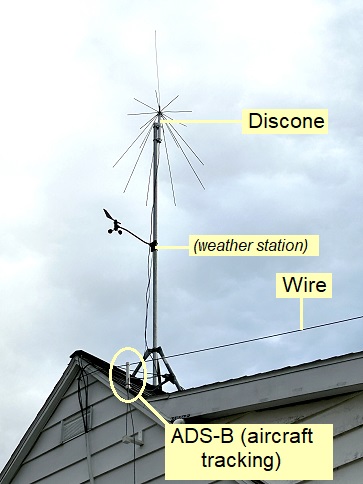

SDRs often come with a small telescoping antenna that attaches directly to the unit; however, these are practically useless for most applications (except for listening to AM/FM broadcast stations, or tuning into nearby devices). For reception below 30 MHz (AM broadcast and shortwave), a random length of wire running outdoors is usually sufficient. For UHF/VHF monitoring (above 30 MHz), I use a roof-mounted discone antenna (the MFJ-1866 currently costs approximately $80). Of course, you will also need coaxial cable to connect the antenna to the radio (usually through a small bulkhead installed at a window). For some types of monitoring (including satellite), additional antennas may be required; for example, a dedicated ADS-B antenna may be desired to extend the range of aircraft tracking from 20-30 miles (using the discone) to 100+ miles (using a $20 weather-proof stripline antenna).

Got questions? So long as they're not *too* technical, I would be happy to assist! Email me: kc2klc@lutins.net.